JT Tait is currently undertaking the Master of Creative Writing, Publishing and Editing at the University of Melbourne and is the mother of a recently turned teenage boy who laughs that they will be finishing uni together.

‘Between Trauma and Beauty Itself’: Mothers, Memory and Forgetting

We tell stories because in the last analysis human lives need and merit being narrated. This remark takes on its full force when we refer to the necessity to save the history of the defeated and the lost. The whole history of suffering cries out for vengeance and calls for narrative

—Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative

First, the elevator. The long ride up in the stench of piss and stale cigarette smoke. The grey metal clunking back to reveal the paint-chipped door of Nanna’s flat.

Mum’s hair long, thick and swinging before my sister and me as she knocks. Nanna, grey curls and wheezing breath, opening the door to greet us. Walk into the dining area, a round table with yellow plastic tablecloth, stiff plastic in folds. Four chairs, brown vinyl peeling back, exposing white tufts like fairy floss, which we would work at nervously while eating lunch or dinner. Brown plastic placemats with yellow flowers sit on the table, matching the floral curtains at the small window. In the middle of the table a gold stork statue holds pride of place. A bench separates the dining room from the kitchen. Here we would eat our breakfast seated on the tall orange stools, Nanna passing cereal and toast over the scratched surface. Homemade sausage rolls baking in the oven, boiled-meat scent swamping the cramped quarters.

On the left the living room, always in darkness with blinds drawn and TV flickering. Dougie sprawled in an armchair. For years we thought Dougie was another word for Grandpa, turns out it was just his name. He was my Nanna’s boyfriend and father to none. But he remained our Dougie.

Go straight through the dining area and into the kitchen, turn left at the second door and you reach a small hallway. I slipped there and hit my head on the wooden frame of the door; vision blood-soaked and reddened, twenty-five stitches right in the middle of my forehead. My cousin did the same thing in the same place a couple of months later. It was the mat at the end of the hallway that did it. We’d come hurtling down in our never-ending rush to be somewhere and the mat would slip right out from under our feet. Nanna got rid of it after the second time.

The kids’ room is first on the left, then Nanna’s room; at the end a sewing room, and on the right a bathroom. Nanna died in the kids’ room. She had an asthma attack. They say she went there to be closer to her grandchildren. I was nine and thought I’d killed her because she’d hit me on my last visit. When I told Mum my fears, she explained that not everything was about me.

That was the first time I saw what a small part I played in the world around me.

***

Nanna lived in the commission flats. An overriding sense of depression clouds my memories of that place.

She had a brother, messed up from the war. She was always slapping the back of his head. He’d just sit there, food dribbling down his chin. He scared us with his vacancy and his constant wet smile.

She fought with Mum and Dad all the time. Said they weren’t fit. Mum said Nanna was an alcoholic. That’s why Mum doesn’t drink.

We used to love it when she gave us money to go to the commission shop and buy mixed lollies. Half-cent lollies, a couple of dollars would go far.

We’d cross the road to Prahran swimming pool and spend the whole day there with our cousins. Just us, no adults nagging. Lips stained red by icy-poles. Afterward we’d take the elevator up to her flat to soak in a warm bath. We’d share the bath, my sister and I. Blowing bubbles in each other’s faces and wearing bubble beards. Then we’d sit beside Nanna on the couch with her aged hands entwined in our water-wrinkled fingers.

I got two black eyes from a girl half my size but twice my age in the playground at the base of the stairs. We knew her as Googie. She was queen muck of the commission play areas. She told me she could see my undies while I was standing on the swing, swaying back and forth, minding my own business. All I said was at least I had some on. My mouth was always getting me into trouble back then. In any case, girls like that don’t take nicely to talk like that. I was six.

There was a forbidden stairwell. Where a man was known to play with himself and watch kids. We would dare each other to run past. Double-dare. Go up the staircase. I dare you. No, you do it. The call of the darkness of that stairwell was a constant black whisper. From the slide in the playground you could see its shadows beckoning us across the way. We had our own mysterious ways of learning life lessons when we were young. The way we’d torture each other with our fears, egging each other on to yet more foolishness.

I can’t remember ever seeing Nanna outside of the dimness of those high-rise walls. We would run wild with our cousins who lived in different commission flats across the way and around the corner. They were so much tougher than us, little flower-children that we were. We wouldn’t come home ’til dinner. Then bath-time and warm in clean pyjamas we’d sit by her side watching TV or reading stories.

Nanna was warm and soft when she hugged you and her clothes smelled of jasmine. Looking back now I think she was trying to make up for something with us, something she missed in raising her own kids.

I came to hate those flats. I hated the way Nanna talked to my parents. She scared me when she spoke of taking us away from them. How she could be so nice and turn so mean in the same breath. But I loved my Nanna. I loved her cooking. I loved that she loved me. I often imagine her surrounded by crayoned drawings, gasping for breath. I hope being close to us, her grandchildren, helped her. Somehow.

***

Funny when writing about Nanna how the child’s voice always comes to play. Time stretches ever onwards yet bounces me back to the girl I was. For I never learned to know her as herself, a separate identity. In ‘Bracha’s Eurydice’—her foreword to Bracha Ettinger’s The Matrixial Borderspace—Judith Butler writes of the loss of Eurydice that ‘the gaze by which she is apprehended is the gaze through which she is banished. Our gaze pushes her back to death, since we are prohibited from looking, and we know that by looking we will lose her’ (viii). Nanna will forever be real only as an extension of my mother, myself. Her story, her rationale for behaving in certain ways, is lost to us. No matter how hard we try to capture her.

Nanna lived in an unforgiving time and place but this doesn’t explain her apparent dislike of only one of her surviving children, my mother. She was of the time when people accepted Freud’s theory that ‘the desire for a child is the desire for a penis, and in this sense, a substitute for phallic and symbolic dominion’ (Kristeva 206). The concept of losing one’s identity after childbirth would have been beyond comprehension. In the Prahran commission flats and pubs no one cared two hoots about the identity of that Irish Catholic mother dragging her six children around, begging for money to feed her children and spending it all on booze. Who was Noreen Fergus? How did she come to be here? I think in another time she would have been a fiery feminist, a passionate activist. Instead she found herself stuck in a patriarchal society with no chance of escape. Nanna was not made to be a mother; I imagine she would have wholeheartedly agreed with the concept of motherhood as ‘a sort of instituted, socialized, natural psychosis’ (Kristeva 206). Kristeva writes:

Pregnancy seems to be experienced as the radical ordeal of the splitting of the subject: redoubling up of the body, separation and coexistence of the self and the other, of nature and consciousness, of physiology and speech. This fundamental challenge to identity is then accompanied by a fantasy of totality – narcissistic completeness – a sort of instituted, socialized, natural psychosis. (206)

All this is wholly imagined however, pieced together from stories told to me by my mother and told to her by hers. Butler begins her foreword by asking: ‘what does one do with early childhood? Or rather, what does early childhood do with us’ (vii)? All those misshapen memories, thwarted by time. How do they leave their mark on us? Who do we become because of them? I do not pretend to have the answers, just an enduring fascination with the complexities of intergenerational trauma.

***

Telling the story of generational addiction can be difficult: the tricks memory plays, the alternate perspectives. Telling one’s own family story can also be construed as self-indulgent. Fear of ridicule, of the dreaded ‘misery memoir’ tag, fear itself; all can skew the words on the page.

My nanna was an alcoholic; my father was an alcoholic and a heroin addict who died of an overdose; my mother is a heroin addict. I have an addictive personality; I am consumed by my passions. And all down this ‘wicked’ line, each addict has despised the others’ addictions.

My sister and I grew up with love in abundance: my mother did not. We all grew up with trauma. Butler writes:

We are speaking … not only of the loss of childhood, or the loss of a maternal connection that the child must undergo, but also of an enigmatic loss that is communicated from the mother to the child, from the parents to the child, from the adult world to the child, who is given this loss to handle when the child cannot handle it, when it is too large for the child, when it is too large for the adult, when the loss is trauma, and cannot be handled by anyone, anywhere, where the loss signifies what we cannot master. (ix).

Such phenomena are handed down to us through the generations, a family gift of unknown origin. Kristeva suggests in ‘Women’s Time’ that ‘there are cycles, gestation, the eternal recurrence of a biological rhythm which conforms to that of nature and imposes a temporality whose stereotyping may shock, but whose regularity and unison with what is experienced as extra-subjective time, cosmic time, occasion vertiginous visions and unnameable jouissance’ (191). Is it possible, within the reverberating tale of our family, there is joy in the sorrow? Are we now so tied to our past that we revel in our peculiar branch of divine melancholy?

In collating these seemingly random memories from my childhood I aim to create an overall sense of that place in time and how its echoes still reach us now. Ricoeur states that plot is first ‘a mediation between the individual events or incidents and a story taken as a whole’ (65). ‘In this respect,’ he goes on to write, ‘we may say equivalently that it draws a meaningful story from a diversity of events or incidents (Aristotle’s pragmata) or that it transforms the events or incidents into a story.’ The story you find behind the non-linear form may tell you more than even I know.

The greatest gift of growing up is, I believe, to meet your parent as a friend. A being beyond the extension of the self. My mother never had that opportunity. When you befriend your parents, much can be forgiven. When you’ve lived and known your own flaws, you can live with and love them in others.

***

First, the smell. Lemons. That sharp tang. It remains one of my first remembered sensations. I’m not sure why heroin cooking smells like lemons but cut one open and I’m transported back to that wide-eyed kid sitting on the staircase of our house in Birchgrove. Watching through the bannisters as Dad loosens the belt around Mum’s upper arm and slowly slides the needle from her vein. I watch her head roll to the side, her eyes grow heavily lidded. He makes sure she’s settled before pulling the loosened belt up his arm and tightening the cracked leather.

My sister comes creeping up behind me and I shoo her away, toward our bedroom. I feel the heavy weight of her lean against me, her stomach on my back, and sense her trying to look over my shoulder. Standing up, I take her hand and walk up the stairs. I look back once to see Dad put the needle in his own arm. I start chattering nonsense and watch my sister’s face light up.

***

In Birchgrove they were dealing. So we had lots of nice things and lived in a two-storey house with bars on all the ground-floor windows.

Our days were structured with lessons in the morning and play in the afternoon. On waking, we’d race down the stairs to find a message and maths sum from Mr Man. Mr Man was a stick figure on the blackboard. Once we’d answered the question we were allowed to wake Mum and Dad up. After breakfast Dad would teach us how to read, do a few more sums, and then focus on music. Dad was a trombone player and composer and he played Jazz.

Afternoons with Mum were endless and lazy play. Twice a week we had a Spanish tutor. Even when they weren’t dealing, the same structure remained. Lessons in the morning, play all day. That is, up until they separated.

We really felt we had the most normal of lives. Most of the time.

***

One day we came home from the shops and the bars on one window were bent. Dad told us Superman had come to visit while we were out. We asked why he’d made such a big mess? Drawers were pulled out of the cabinet and cushions were off the couch. Chairs were tipped over. Our Lego was spilt across the floor and Dad swore as he stepped on a piece. Mum put her bags on the floor in the hallway and quickly started tidying up. I went with my sister to the window and looked at the bent bars, our eyes filled with marvel. It was the side window in the lounge-room. We could see down the long garden pathway to the vegie patch. One of next-door’s rabbits hopped amongst the lettuces. My sister went to tell Dad, but I shushed her with a finger across her lips. I could feel something was wrong by the pressure on my back, my shoulders. I could sense something fearful behind their furious whispering. I grabbed her hand and pulled her across the room, up the stairs. Let’s play.

All was forgotten by dinner when we ate our lentils at the worn wooden table. Dad kicked up his feet and pulled the guitar onto his lap, softly tuning and humming under his breath. Mum started piling the dishes into the sink, flicking us with the tea towel to make us laugh. Bent spoons clattered into soapy water. Becky told Dad about the rabbits. Dad hooted and ran out to the back garden, making wild gestures and yelling. Taking the pesky rabbits to task. We followed laughing and he piled our crossed arms with ripe veggies. We dumped them on the kitchen table and Mum shooed us away, fondly grumbling about the mess. We sighed into our soft beds that night, safe and grateful for all things normal and comical.

The bars on the windows didn’t help when the cops busted us. They just put a ladder up to Mum and Dad’s balcony and entered through their bedroom door. The first I knew of it was the shouting. Gruff voices, violent. Then two police officers entered our bedroom, came up to our bunk bed. They told us everything was going to be okay. But I could hear the thuds and short breaths. I could hear my Mum screaming at someone to stop. And the faint sound of my Dad whimpering.

The next day Mum sold everything we owned to get Dad out on bail. It was the first time we got busted, but it wasn’t the last.

Living with addicts from a young age, you love them even when they’re hurting you and you don’t know it. The days they OD’d in front of us – mostly accidental, occasionally purposeful: dragging them to the shower and drenching them in cold water, the mad rush to the next-door neighbour for help, the ambulances, the misguided reassurances from adults who thought we knew nothing. The long hospital visits, the foster carers, the threats from family members to take us away.

Above all: an ever-abiding love and a longing to never be separated. Ever.

***

I was twelve when I first started wanting to write our story. Back then I wanted two things: I wanted to let other children of addicts know they weren’t alone, and I wanted people to understand addicts. I was tired of living a secret life. Of being afraid of being found out. I wanted to bust it open and just be. I wanted people to love my parents. Basically, I wanted to live without stigma before I knew what stigma was. Kristeva asks why we yearn to use literature as a means of affirmation: ‘is it because, faced with social norms, literature reveals a certain knowledge and sometimes the truth itself about an otherwise repressed, nocturnal, secret and unconscious universe? Because it thus redoubles the social contract by exposing the unsaid, the uncanny?’ (207) Perhaps at twelve I sensed that in making a game of the ‘frustrating order of social signs’ (Kristeva 207), I would in sense be making a place for myself, my family.

It was then that I realised I could never know my own story without knowing theirs. My parents’. Kristeva talks about how to ‘bring out … the singularity of each person and, even more, along with the multiplicity of every person’s possible identifications (with atoms, e.g., stretching from the family to the stars) – the relativity of his/her symbolic as well as biological existence, according to the variation in his/her specific symbolic capacities’ (210). We are all we are through a combination of biology and chance and hold a certain responsibility to represent our unique circumstance. So I bugged my parents day and night and I wrote down every word. All the hurt, all the mistakes, all the hopes and failed dreams. I gathered them and hoarded them like small treasures. But of course I was twelve, and didn’t yet know I’d make many mistakes of my own.

It was not pleasant, I am sure, to have one’s child ask the sorts of questions I did. But my parents had a knack for brutal honesty, which they delivered with a rhythmic beauty. Perhaps a perverse pride in their child’s inquisitiveness was also on display.

Growing up ‘on the wrong side of the tracks’ also lent my writerly aspirations a bent and socially awkward tangent. Exposés of the kind that poured from my pre-teen pen were unexpected to say the least. Ricoeur states that,

as a function of the norms immanent in a culture, actions can be estimated or evaluated, that is, judged according to a scale of moral preferences. They thereby receive a relative value, which says this action is more valuable than that one. These degrees of value, first attributed to actions, can be extended to the agents themselves, who are held to be good or bad, better or worse. (58)

The reader, then, bases a character’s worth on the ethical nature of their actions. For Ricouer, ‘There is no action that does not give rise to approbation or reprobation, to however small a degree, as a function of a hierarchy of values for which goodness and wickedness are the poles’ (59). But who decides these moral values? And can one thwart these values once embedded?

The aim of my twelve-year-old angst was to turn wickedness on its head and show the banality and ordinariness of an addict’s life. It was not a cry for help, for saving. It was a desperate plea for understanding. The years fly by and slowly the world awakens to hear the voices it has silenced for so long. Now, forty-plus, I still write to break open addiction taboos, though many have already been broken. I still struggle to find the right words. Simone de Beauvoir writes:

Old age. From a distance you take it to be an institution; but they are all young, these people who suddenly find that they are old. One day I said to myself: “I’m forty!” By the time I recovered from the shock of that discovery I had reached fifty. The stupor that seized me then has not left me. (672)

I look in the mirror and see Beauvoir’s words reflected back to me, to my mother, to my grandmother. And to all those mirror images I say, forgive yourself. Forgive.

***

The story of my Nanna’s dying words has become mythological. I’ll never truly understand the power she had over my mother. Her stories of abandonment and loss are etched into my brain. Every hurt word, every dismissal, every avowal of hatred from her mother’s mouth. And so my mother chooses her needle, to forget. She gives me her stories and I keep them safe. Her stories become mine but are not me, they imprint. Butler suggests that such stories are indeed ‘never fully made one’s own, for the claim of autonomy would involve the losing of the trace. And the trace, the sign of loss, the remnant of loss, is understood as the link, the occasional and nearly impossible connection, between trauma and beauty itself’ (xi). And I choose to not lose the trace, to remember.

The memories shift and change, as does my perspective within them. Sometimes I see the stories as from a great distance. At other times I’m right inside them, living and breathing each moment as it happens.

My Nanna’s last words were an affirmation of all my mother’s greatest fears. But also an inspiration that changed the way she parented, so changing the arc of her story. I inherit the trauma and beauty both.

***

First, the shaking. It was the middle of the night when Mum woke us. Rain pelted against the window leaving glistening trails against a backdrop of darkness.

All is confused and jumbled as I swim into focus. I sit in bed rubbing my eyes, noting the panic in her voice as she shakes my sister awake. The bedside lamp sends a soft glow of purple around the room, shining through the scarf draped over it.

Wake up. Nanna’s dead. We have to go to the flats. I ask if she’s kidding. Well, that wouldn’t be a very funny joke would it, she snaps. It’s unlike her and so I know this is Real. I stumble out of bed and let her bundle me into a dressing gown and slippers. I must’ve fallen asleep because suddenly I’m awake in the back seat of the car. My head leaning against the window, the rain now in a hurry across the pane. Mum and Ava are arguing in the front. Ava steers erratically and beeps the horn loudly, gesturing rudely out the window. Mum cries.

***

Mum and Dad had been separated for a few years when Nanna died. Mum had stolen us away in the dead of night, barely packing a thing. First we’d travelled to our friends in Queensland, but he’d found us. Then she went to hospital to get clean and sent us with a friend to Melbourne, to live with Nanna until she got better.

When Mum arrived we moved in with her girlfriend Ava and they shared a bed. Then she cut off her long hair. We didn’t cry until we saw her short cut. It seemed the final straw. Too many changes and too quick. That hair we’d seen swinging before us all our short lives. We’d played with it and poured honey in it when she wouldn’t wake up. It seemed to signify who she was, and now wasn’t. We had to adjust ourselves to this new Mum, and figure out our place in the world beside her.

Dad followed us eventually. He was arrested in Sydney for attempting suicide so couldn’t come straight away. That’s what I overheard, or thought I overheard. When he arrived and came to see us, Ava left a note on the door saying NO MEN ALLOWED. When we stayed at his house next and they came to pick us up, he left a note on the door saying NO AVAS ALLOWED. And so it went.

***

When we arrive at the flats, we take the elevator up one last time to Nanna’s. This time, instead of Mum’s long hair before us, there is Mum and Ava’s hands holding each other in fists. There is no Nanna with wheezing breath to greet us at the door. One of our uncles opens the door abruptly after the first knock. Mum hugs him briefly and walks in. He ignores Ava’s outstretched hand. We appear forgotten so straggle in quietly and lean against a wall.

The dining room is too small for all of them. All their bodies too grown for the space in which they’d grown up. There is muted conversation and a thick layer of smoke across the ceiling. The gold stork stands on the table amid a crowd of bottles, stretching its neck gracefully over bourbon and rum, wine and beer, overflowing ashtrays. We slide down the wall and sit on the floor, huddled together. They seem like brooding giants from that angle. And it isn’t just sorrow I felt from them in that confined space but menace also. Something angry simmering below the surface talk. Something in the way her brothers held themselves frightened me.

I heard Mum asking where she was and someone reply the kids’ room. Her sister walked with her towards the hallway. We just sit, watching. Ava stands to the side of the room, completely forgotten. I can hear Mum crying in the other room. Loud sobs.

It was then I saw Dougie. But he was no longer our Dougie. He was filled with some emotion I couldn’t place. It made him dark. He gloomed. He came through the dining room at a pace I’d never seen him take. I heard him say something guttural in the next room. Then my mother screamed. A never-to-be-forgotten type of scream. The room erupted. All of them shouting at each other, so many words unknown. All jumbled on top of one another. But my aunt’s whisper carried through it all. He told her. Mum strides into the room, stopping suddenly and staring at the table. At the gold beak of the stork rising above the bottles. As she leans forward, I can see a faint line of sweat across her forehead, her eyes red. She picks up the stork and walks straight out. Ava gathers us up and we take one last look through that paint-chipped door at all our family before they slam it shut behind us.

In the corridor Mum is punching the elevator button. Ava tries to hug her and is pushed away. I don’t think she remembered in that moment that we existed. The grief is too much. We take the elevator down and we never see that place or those people again.

WORKS CITED:

Butler, Judith, ‘Foreword: Bracha’s Eurydice’, in Ettinger, Bracha L., The Matrixial Borderspace, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

de Beauvoir, Simone, Force of Circumstance, Middlesex: Penguin, 1968.

Kristeva, Julia, ‘Women’s Time’ in Toril Moi (ed.), The Kristeva Reader, New York City: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Ricoeur, Paul, Time and Narrative, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University.

Lindsay Tuggle has been widely published in journals and anthologies, including: Cordite, Contrapasso, HEAT, Mascara, Rabbit, and The Hunter Anthology of Contemporary Australian Feminist Poetry(2016). She was short-listed for the University of Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s International Poetry Prize, judged by Simon Armitage. Her work has been recognised by major literary awards, including: the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2015), the Val Vallis Award for Poetry (second prize 2009, third prize 2014), and the Canberra Vice-Chancellor’s Poetry Prize (shortlisted 2016, longlisted 2014). Her first collection, Calenture, is forthcoming with Cordite Publishing. The manuscript evolved from residential writing fellowships awarded by institutions including the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Mütter Museum of Philadelphia. Tuggle also writes on intersections of poetry and science. The University of Iowa Press’s Whitman Series invited her first book, The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America (forthcoming in 2017). She wrote a chapter on ‘Poetry and Medicine’ for Cambridge University Press’sWhitman in Context (2017). She teaches literary studies at Western Sydney University. Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com

Adolfo Aranjuez is editor of Metro, subeditor of Screen Education, and a freelance writer, speaker and dancer. He has edited for Voiceworks and Melbourne Books, and been published in Right Now, The Lifted Brow, The Manila Review, Eureka Street and Peril, among others. Adolfo is one of the Melbourne Writers Festival’s 30 Under 30. http://www.adolfoaranjuez.com Writing to the Wire

Writing to the Wire Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine.

Mindy Gill completed her Honours in Creative Writing at QUT. She has won the Tom Collins Poetry Prize, a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Voiceworks, Tincture, Hecate, Australian Poetry Journal, and Island Magazine. She is an editor at Peril Magazine. Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers.

Laura McPhee-Browne is a writer and social worker from Melbourne, Australia. She is currently working on what she hopes will be her first book, ‘Cooee’, a collection of echo stories inspired by the short fiction of her favourite female writers. Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth.

Jessica Dionne lives in North Carolina and is currently pursuing an MA in Literature from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She recently presented poems at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association annual conference in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and her work has been featured in The Longleaf Pine, Luna Luna Magazine, and Pour Vida Zine, and is forthcoming in The Mayo Review, and Rust + Moth. Exhibits of the Sun

Exhibits of the Sun We Need New Names

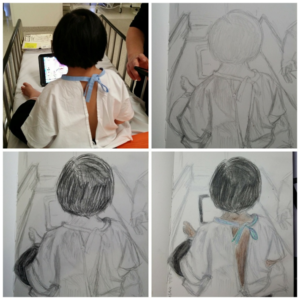

We Need New Names CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

CB Mako is a member of West Writers Group and art student at Footscray Community Arts Centre.

The Herring Lass

The Herring Lass The Historian’s Daughter

The Historian’s Daughter Derrida’s Breakfast

Derrida’s Breakfast  Owen Bullock is a PhD Candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Canberra. His publications include

Owen Bullock is a PhD Candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Canberra. His publications include  Anita Patel was born in Singapore and lives in Canberra, Australia. She has had work published in the Canberra Times, in Summer Conversations (Pandanus Books, ANU), in Block 9, Burley Journal, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and Demos Journal and by Wombat Books. Her children’s poems have been published in the NSW School Magazine and in an anthology Pardon My Garden edited by Sally Farrell Odgers and published by Harper Collins. She won the ACT Writers Centre Poetry Prize in 2004 for her poem Women’s Talk. She has performed her poetry at many events, including the Canberra Multicultural Festival and the Poetry on the Move Festival (University of Canberra). She was the feature poet for the Mother Tongue Showcase at Belconnen Arts Centre, June 2016.

Anita Patel was born in Singapore and lives in Canberra, Australia. She has had work published in the Canberra Times, in Summer Conversations (Pandanus Books, ANU), in Block 9, Burley Journal, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and Demos Journal and by Wombat Books. Her children’s poems have been published in the NSW School Magazine and in an anthology Pardon My Garden edited by Sally Farrell Odgers and published by Harper Collins. She won the ACT Writers Centre Poetry Prize in 2004 for her poem Women’s Talk. She has performed her poetry at many events, including the Canberra Multicultural Festival and the Poetry on the Move Festival (University of Canberra). She was the feature poet for the Mother Tongue Showcase at Belconnen Arts Centre, June 2016. Kay Sexton’s fiction has appeared in over 70 anthologies and literary magazines. Her recently published novel, Gatekeeper, was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize and in addition to being shortlisted, finalist or winner of many literary competitions she has had two non-fiction books on gardening published. This is remarkable given that her sole ambition as a child was to become a librarian so she could read all the books ever written, rather than writing anything.

Kay Sexton’s fiction has appeared in over 70 anthologies and literary magazines. Her recently published novel, Gatekeeper, was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize and in addition to being shortlisted, finalist or winner of many literary competitions she has had two non-fiction books on gardening published. This is remarkable given that her sole ambition as a child was to become a librarian so she could read all the books ever written, rather than writing anything. Karen Whitelaw is a Newcastle-based writer and teacher of creative writing. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies, including Cutwater Literary Anthology, Newcastle Short Story Award 2012, Award Winning Australian Writing 2016. Her flash fiction has been performed at Newcastle and Sydney Writers’ Festivals, and made into a visual presentation. She has completed a Master of Creative Arts at the University of Newcastle. She is currently working on a collection of short stories.

Karen Whitelaw is a Newcastle-based writer and teacher of creative writing. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies, including Cutwater Literary Anthology, Newcastle Short Story Award 2012, Award Winning Australian Writing 2016. Her flash fiction has been performed at Newcastle and Sydney Writers’ Festivals, and made into a visual presentation. She has completed a Master of Creative Arts at the University of Newcastle. She is currently working on a collection of short stories.

Getting By Not Fitting In

Getting By Not Fitting In Have Been And Are

Have Been And Are